Home Main Index Introduction Contact Us

|

▪ Silver ▪

Silver and gold are the best materials for jewelry, flatware (knives, forks, spoons and serving pieces), and holloware (originally defined as vessels that enclose space such as bowls, vases, and pitchers, but generally expanded to include objects like trays and picture frames). Both metals were discovered in their raw, native states millennia ago. Both were extracted from ores by early smelters and refiners. Both were revered by alchemists (whose symbol for silver was the crescent moon shown here).

Both are highly ductile (able to be drawn into thin wires) and malleable (able to be pounded flat and hammered into shapes that retain their form). They have high melting points and are easily worked. Both have an attractive luster. Both are fairly impervious to oxidation and corrosion, and are known, along with the so-called platinum group (iridium, osmium, palladium, platinum, rhodium, and ruthenium) as the "noble" metals. They're also called "precious" metals because of their durability and relative scarcity. Silver has the added property of photosensitivity to visible light and high-energy radiation, and was widely used by the photographic industry.

While silver is precious, and has been a traditional store of wealth for many millennia, its value is approximately 1/50th of that of gold. Sultans and CEOs can afford gold tableware, but for most of us, decorative luxury means silver. Until recently, Wallace Silversmiths sold a pattern called Grande Baroque in 18K gold. A single 5-piece setting cost roughly $30,000. A full 192-piece Continental gold flatware set would have set you back just under a million (only two complete sets were ever sold).

A nice neighborhood -- On the Periodic Table, silver is surrounded by other precious and useful metals

Silver is the 65th most abundant element in the earth's crust (19 times more common than gold). The word "silver" derives from the Anglo-Saxon word siolfur or seolfor. Its atomic symbol is Ag, short for the Latin Argentum. It conducts heat and electricity better than any other metal, and is the most reflective of all elements. Only gold and possibly palladium are more malleable. Silver is an important part of "green," "white," and "yellow" gold used in jewelry. Since pure silver is fairly soft, it is commonly alloyed with more than a dozen other metals -- most commonly copper -- for a wide range of industrial uses.

Some scientists believe silver bromide was used to fake the image in the Shroud of Turin. Silver chloride can flush mercury from the human body. Tiny bits of hair-trigger silver fulminate are used in explosive noisemakers. In a compound with Iodine it's even dropped out of airplanes to seed clouds and make rain.

Blue Man

For many years silver was the first element that touched us all. A dilute solution of silver nitrate was routinely applied to newborn infants' eyes to combat disease. While still used for this purpose, it burns slightly and is being supplanted by antibiotics such as Erythromycin. In its pure form it is non-toxic to humans, although in high doses it can cause an alarming condition called argyria, which causes the skin to turn grey or even grey-blue. In 2002 an (unsuccessful) Libertarian senatorial candidate in Montana, Stan Jones, gained notoriety for his ashen blue-grey argyriac skin that resulted from application of a home-brewed colloidal silver remedy. He had used this nostrum in the misguided fear that the Y2K bug would prevent the manufacture and distribution of antibiotics.

Silver is the whitest of all minerals, and one of the most highly reflective. It has been long used to make the best mirrors, which may explain why alchemists referred to it as luna (gold was sol for the sun).

Wired

Silver is the best electrical (and thermal) conductor, and is prized for electrical contacts in volatile environments because it will not arc or spark, even when tarnished. This makes it valuable in spacecraft and aircraft. During WWII, the Manhattan Project built an enormous processing facility in Oak Ridge, Tennessee called Y-12 to enrich uranium. Since the weapon-form isotope of uranium (U-235) is chemically similar to the much more common non-fissile variety (U-238), and is intermingled with it in nature, physical means are required to separate the two. The Y-12 facility contained several large racetrack-shaped electromagnetic separators or "calutrons," giant electromagnets that deflected the slightly heavier stream of charged U-238 particles into one collector and their slightly lighter U-235 cousins into another. Normally the windings for these would be made of copper wire, but copper was needed for war munitions. So the scientists borrowed 14,700 tons of pure silver from the Treasury to fabricate the wire and bus bars for the enormous magnets.

One of the Manhattan Project's Oak Ridge calutrons, which used several billion dollars' worth of silver wire and connecting bars made from bullion borrowed from the US Treasury

Silver has been used as coinage for more than two millennia. Until 1968 you could take a United States "silver certificate" dollar bill to a US mint office and redeem it for a small envelope (.77+ ounce) of small silver pellets or "granulations." Until that decade, high-value US coins were made of a silver alloy, but heavy industrial and military demand and rising prices for the metal forced the government in 1965 to reduce (and then in 1970 to eliminate) the silver content.

Greed

In a fascinating tale of wealth and greed, Nelson Bunker and William Herbert Hunt, sons of the fabulously wealthy oilman H. L. Hunt, once tried to corner the market (own so much of something that they can illegally manipulate the price) on silver in the 1970s. They began buying silver contracts in 1973 when the price was below $2 an ounce, and joined forces with two Saudi sheiks to buy as much as they could, eventually owning a third of the world's reserves according to some sources. This helped drive the silver price skyward until it reached nearly $50 an ounce in January, 1980. The commodities trading exchanges reacted by first changing their trading and margin rules and then stopping silver trading. On March 27th of that year, now referred to as "Silver Thursday," the price collapsed.

The Hunts actually took possession of much of their silver rather than just owning it on paper. They feared the government might grab or tax it, and initially stashed 40 million ounces of it in Switzerland after a Hollywood-worthy late-night caper involving three chartered cargo jets, a platoon of armored cars, and gun-totin' cowboy sharpshooters to guard the Croesian hoard. Later speculators like Liberal firebrand George Soros, who pocketed over a billion dollars in a single day by betting against the British pound sterling and "broke the Bank of England" in 1992, did it without physically touching an ingot.

(Croesus, whose name is now synonymous with grand wealth, was the king of Lydia in present-day Turkey, and was said to have been the first to issue coinage -- in gold, silver, and a naturally occurring gold-silver alloy called electrum -- during his reign in the 6th century BC. Unfortunately for him, after a legendary consultation with the Oracle of Delphi, Croesus made an unsuccessful bid against the Persian empire and was nearly burned at the stake. By some accounts, his flaming pyre was extinguished by a sudden rainstorm.)

Meltdown

One important consequence of the Hunts' speculative foray was that a great amount of silver flatware and holloware was forever lost to the smelter. The frenzied rise in price caused large numbers of people to melt down their heirloom silver and sell it as bullion. Presumably this affected Arts & Crafts silver to a significant degree, since back then Arts & Crafts metalwork was severely underappreciated and undervalued, and heavy (which meant it would bring more money), and since many owners foolishly interpreted the planished, handmade, sometimes rustic surfaces and forms as signs of little artistic worth.

In fact, in a 1980 New York Times article, a Sotheby's expert noted that Kalo and Lebolt pieces were still bringing in prices "just above their melt value."

1Used primarily in ingots and investment-grade coins, is sometimes made into holloware 2Electrum is an alloy of silver and gold found in nature. It is somewhat like "white gold" today 3German silver has no silver content -- it is made of copper, nickel, and sometimes zinc and is often called "nickel silver."

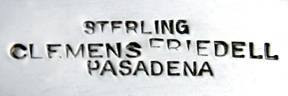

Gold is commonly measured in karats (K), which makes it easy to determine the purity of the alloy (24K is 100% gold, 22K is 91.66% gold, 18K is 75% gold, 14K is 58.33% gold -- the British version, 585 or London Gold, is 58.5%). Silver fineness has no equivalent standard designation and is commonly referred to with terms like "Sterling" and "Coin." The non-silver alloy component is most commonly copper. Purity is set by governments, and can be determined by assays. The most famous modern assay was done in London in 1702 by the director of the London mint, who happened to be Isaac Newton.

Sterling silver, the standard used today in England and the United States, is 92.5% silver and 7.5% copper. The name "sterling" came either from "Easterling Silver" after coinage in a region in Germany, or from the French word esterlin. In the 12th century, England's Henry II is said to have adopted the 92.5% silver coinage alloy of the prosperous German Hanseatic League, located in an area called the Easterling. In 1300 Edward I decreed that all English silver be of sterling quality, and adopted the Leopard's Head sterling assay mark for London still in use today. The British lion passant (facing left with a raised paw) assay mark indicating sterling content was adopted in 1545. A slightly higher 95.84% Britannia standard was introduced in 1697 to thwart the melting of silver coins by silversmiths, but the sterling standard returned in 1720. Originally, a Pound Sterling (£) was the actual worth of a pound of pure silver.

In 1976 the National Stamping Act in the United States gave gold importers a little wiggle room in marking fineness, allowing lower purity up to half a karat less than specified. The Act gave jurisdiction over such matters to US Customs and the FBI. With silver it specified a more stringent standard -- the content cannot be more than 0.004 (four parts per thousand) below the standard specified. Some gold today is marked with a "P" (for plumb) to indicate precise fineness. Without it, 18K gold could actually be 17.51 karats instead. 18KP means the 18 karat fineness is right on the money.

90% silver coins are sometimes used in sterling items -- this paperweight by Leonore Doskow is a good example.

The biggest silver producers are Mexico, Peru, and Australia. Worldwide, mined silver ore accounts for just a quarter of all new production (much silver is recycled). The rest is a by-product of mining for gold, lead, copper, and zinc. The state of Nevada (site of the historic Comstock Lode, the richest US silver discovery ever) produces around a third of all domestic silver, leading the pack.

Mother Lode

The Comstock Lode is said to have been found or at least claimed in 1859 by three people -- Henry Comstock (more a gutsy interloper than an actual discoverer), Peter O'Riley, and Patrick McLaughlin. (Some say it had actually been discovered by two Grosh brothers who died under mysterious circumstances two years earlier.) O'Riley and McLaughlin were gold miners who found silver almost by accident (it was in the form of dark blue muck that clogged their gold mining equipment, and turned out to be almost pure silver). None of the three became fabulously wealthy. Comstock went bust and shot himself. O'Riley did better than the others, but eventually lost his wealth, went nuts, and died in an asylum. McLaughlin squandered the little he earned and died after a succession of odd jobs. The mine produced so much wealth that President Lincoln pushed through Nevada statehood even though it technically wasn't populous enough, and the Lode had an important role in financing the Civil War. The federal government later opened a new branch of the US Mint in nearby Carson City to exploit the flow of newly mined precious metal, much of it in the form of silver Morgan dollars, sometime called "cartwheels."

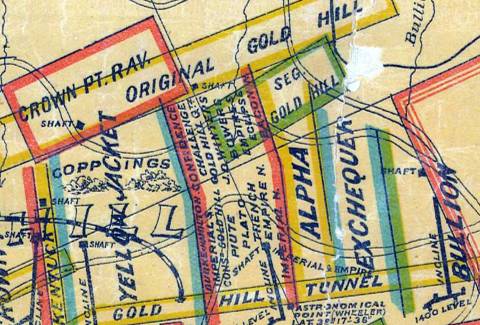

The mining bonanza attracted hordes of prospectors from around the world, many businessmen eager to exploit them, and a journalist named Sam Clemens who chronicled much of this for the Territorial Enterprise newspaper in Virginia City and while doing so adopted the pen name Mark Twain. You can read a chapter from Roughing It about Twain's Virginia City "silver fever" here.

Detail from 1875 Comstock Lode & Washoe Mining Claims Map FROM THE MARY B. ANSARI MAP LIBRARY, UNIVERSITY OF NEVADA, RENO ftp://nas.library.unr.edu/Keck/HistTopoNV/Historic_Maps/comstock_lode_washoe_mining_claims.jpg

The US is the largest market for silver, mostly for photographic and industrial purposes. Apart from its investment and decorative uses, silver is important in dentistry, as a catalyst, as a medical antiseptic, in printed circuits, as a protein-indicating stain for microscope slides, in pottery glazes, as a burn cream, as a water purifier, in silicon photovoltaic cells to generate electricity, as a window coating and defroster, for soldering and brazing, and in high-quality bearings, batteries and mirrors. The rise in popularity of digital photography will almost certainly result in less use of traditional silver-based photographic materials.

Tarnish, Care, and Cleaning

While silver is fairly impervious to oxygen and water (two of its important industrial qualities), it does react with sulfur to produce silver sulfide or "tarnish." This is especially troublesome when silver pieces are stored near kitchens, since many foods (like eggs and onions) contain sulfur, and since the odorant in cooking gas also contains sulfur. This airborne sulfur easily darkens silver surfaces. Sulfur is also present in wool, latex, rubber bands, foam rubber, and carpet-padding and felt made from wool. Chlorides can also be a problem, so keep salt away from silver (which can be tough when using sterling salt shakers). And sticky tape can leave a nasty residue.

The best way to remove light tarnish is to use a brand-name silver cream with its soft foam applicator packed inside the cream container, or a horsehair silver-cleaning brush, and lots of gentle elbow grease. Removing tarnish means removing the very top layer of silver, so don't overdo it. And some silver makers intentionally use chemical blackeners to provide contrast or highlight delicate details, especially in crevices and around engraved or chased areas. Don't try to scrub these away.

Mary Gage used a darkening agent such as Liver of Sulphur to provide highlights in the applied details at the bottom

It's important to get rid of tarnish early, while it's still a light-brown color. Heavy black tarnish can require mild abrasion, and it's better to have silversmiths professionally clean pieces that are dark and discolored. Dips are a bad idea -- they contain acids and can pit surfaces and harm other materials like wood, pearls, ivory, or stones. Don't keep silver out in freshly painted rooms, or near windows or air conditioners that can draw in sulfurous exhaust gasses from outside fossil fuels.

Wash your hands before cleaning or handling silver to remove grease from your skin. Rinse pieces after washing, and dry them carefully. When drying, don't use paper towels, which contain scratchy fibers. Instead, use soft 100% cotton towels or diapers, washed in gentle detergent without fabric softeners or drying agents. Don't use rubber gloves. And don't put silver in the dishwasher.

Silver should be stored in places away from the kitchen, where the air exchange is minimal -- in sealed chests, glass cabinets, or wrapped in acid-free paper (not newspaper!) inside airtight Ziploc bags. A better alternative than paper is silvercloth, soft fabric that contains tiny grains of silver that catch the airborne sulfur before it has a chance to reach your heirlooms.

Firescale

Some sterling pieces exhibit a dull, slightly ruddy stain or "bloom" called firescale, formed where oxygen reacts under heat with copper in the alloy to form red cuprous oxide and then black cupric oxide. A piece with firescale needs the services of a professional silversmith, who can heat and then "pickle" the piece in acid to dissolve the copper. It's also possible to silverplate the item, covering up any scale, but this can create a surface that is shiny and new-looking, and can cover old patina and intentional oxidization.

Don't confuse slightly coppery firescale with orange areas that sometimes peek through the thin surface on silverplated items that have been abused or cleaned too aggressively. Silverplate is usually marked with a stamp like EPNS (for electroplated nickel silver), EPWM (electroplated silver on white metal), EPBM (electroplated silver on Britannia metal), EPC (electroplated copper), or Quadruple Plate.

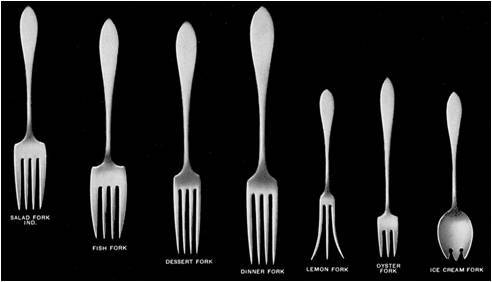

Selection of forks -- see our illustrated utensil guide

Custom

Silver has always been a fairly portable (and showy) repository of affluence. In the indulgently prosperous era around the turn of the 20th century, conspicuous consumption and extravagant displays of wealth were common among the well-to-do. (There was little or no income tax back then. Fortunes blossomed as America grew. In 1895 the Supreme Court struck down an attempt the previous year to create an income tax, and it took the 16th Amendment in 1913 to put one in place. Back then less than one percent of the population paid any income tax at all.)

Lavish multi-course dinner parties required huge sets of dedicated-purpose silver serving pieces. Silver flatware sets became unwieldy as meals soon demanded ranks of special utensils. Instead of soup spoons you had to choose between bouillon, cream soup, or gumbo spoons. You might have to pick out the proper fork from an array that included a dinner fork, salad fork, grill fork, pastry fork, terrapin fork, and strawberry fork, and the food might be served from a beef fork, cold meat fork, bacon fork, jelly knife, cheese server, cake fork, tomato server, asparagus fork, lemon fork, pea spoon, cucumber server, toast fork, chocolate spoon, ice cream slice, orange knife, or olive spoon.

Timeless Works of Art

This befuddling array of flatware was accompanied by odd silver vessels and bowls of all description, each with the sole function of holding a particular liquid or exotic viand. An ornate sterling centerpiece often crowned the table, as men and women seated around it fiddled in their pockets and handbags with silver cigarette boxes, cigar cutters, pipe reamers, calling card cases, perfume bottles, compacts, pill boxes, watch chains, eyeglass holders, match safes, and money clips. Even moderately luxurious offices flouted silver accoutrements.

Kalo navette-form silver box with coral and applied leaf detail -- a work of art

But when the Depression destroyed fortunes and battered the middle class in the 1930s, silver began to lose its cultural luster. It was hard to justify buying a new terrapin fork when the wolf was at the door. Many silversmiths folded or nearly went out of business. When the economy eventually rebounded, they found it difficult to find qualified metalworkers. The fast-paced era that followed was not one for leisurely meals with a dozen courses. You didn't need custom-pounded flatware to choke down a TV dinner. Consumers displayed their wealth through trophy homes, cars, vacations, and clothing rather than dinnerware, and spent their money on entertainment centers and backyard barbecues instead of handwrought claret pitchers. Silver was thought of as too much trouble. Their grandparents may have had servants to polish and serve their sterling, but only the super-rich do today.

We feel the best American silver work was done during the Arts & Crafts movement. While it's true that the silver fabrication in other periods was often done at a supremely accomplished level, those pieces often appear dated and old. However, Arts & Crafts makers produced objects with clean lines and timeless designs that were instant classics when they were made, and seem current today. They are little timeless works of art. Click here to go to the main index Click here to return to the introduction

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||