Home Online References Main Index

▪ Jewelry in the Arts and Crafts Movement ▪

|

|

In 1909, Julius Wodiska wrote a fascinating book entitled A Book of Precious Stones whose goal was to "gather together … information of all sorts about precious stones and the minerals which form their bases … to include all of the many aspects of [t]his subject, and, at the same time, to present it in such form that it may serve at once as a guide to the professional jeweller, a book of reference to the amateur, and yet prove of equal interest to the general reader."

While the majority of the book focused on "the subject of precious stones and precious metals, their artistic treatment apart and combined, their importance in society, commerce, and the arts, their part in the wealth of individuals 'and nations," Wodiska included an interesting chapter called "Jewelry in the Arts and Crafts Movement."

This chapter provided important information on some of the leading Arts & Crafts jewelers at the turn of the twentieth century such as Frank Gardner Hale, as well as on the schools that trained many of the students who would become the mainstays of the movement in later years.

Wodiska's emphasis throughout is on the jewels themselves:

"FROM the earliest ages jewels have powerfully attracted mankind, and the treatment of precious stones and the precious metals in which they are set, often serves as important evidence, not only concerning the art of early times and peoples, but also concerning their manners and customs. Jewels have been the gifts and ransoms of kings, the causes of devastating wars, of the overthrow of dynasties, of regicides, of notorious thefts, and of innumerable crimes of violence. The known history of some existent famous gems covers more years than the story of some modern nations. Around the flashing Kohinoor and its compeers cluster world-famous legends, not less fascinating to the general reader who loves the strange and romantic, than to the antiquary or the historian or the scientist. These tales of fact or fiction are fascinating in part, because they associate with the gems fair women whose names have become synonymous with whatever is beautiful and beguiling in the sex. In the mind of the lowest savage, as in the thought of man in his highest degree of civilisation, personal adornment has always occupied a prominent place, and for such adornment gems are most prized. The symbolism and sentiment of the precious and semi-precious stones, and precious metals, permeate literature. Jewels have their place in the descriptions of heaven in the sacred writings of almost every people that has attained to a written language."

And much of the book details the properties of gems and minerals, as well as their discovery and handling, and includes quaint photos of diamond sorters:

|

|

as well as diamond cutters in the west:

|

|

and the east:

|

|

The chapter on Arts & Crafts jewelry [included in full text below] contains valuable insights and information about the Arts & Crafts movement and some of its best craftspeople:

Jewelry in the Arts and Crafts Movement

THE sequence to the cutting of a gem is generally mounting and setting it, unless it is merely perforated and strung as a bead or hung as a pendant. Mounting and setting is the trade of the jeweller or goldsmith, and whether his goods are artistic or inartistic depends to a great degree upon the discrimination of buyers. There is almost as much variation in the metallic environment of gems as there is in architecture, and the designing and execution of the jeweller range from meritorious to atrocious. To a great extent the metal mountings for gems are stamped out in dies or are otherwise machine-made, but no matter how deserving of praise the original design, the finished article, to the eye artistic, is "commercial." Within a few recent years the struggle to elevate art, in other directions than in the field of things considered as exclusively its province, has invaded the domain of jewelry, and some patient workers have produced commendable creations by their handicraft. This new jewelry is partly identified with what might be termed the general arts and crafts movement, but, as is always the case with efforts of this kind that become known under a popular name, many unworthy deeds are done under its banner by the deceptive, the careless, or the undisciplined, whose products, heralded by them as "artistic," are worse than "commercial." Pretenders can easily impose upon the uneducated. But honest efforts are being made by pioneers with high ideals to properly instill them into the minds of student craftsmen, and to train their hands to a degree of skill that will measure up to the higher standard, which hopeful reformers are trying to set for the jewelry of the future. The efforts of these idealists of the arts and crafts movement deserve the encouragement, the respect, and the co-operation of gem dealers and of the jewelry trade throughout. As it has been well said by Professor Oliver Cummings Farrington in his Gems and Gem Minerals:

"There is room, however, for the development of a much higher taste in these matters than exists at present. The average buyer is content to know that the article which he purchases contains a diamond, sapphire, or emerald, representing so much intrinsic value, without considering whether the best use of it, from an artistic point of view, has been made; or whether for the same outlay much more pleasing effects might not have been obtained from other stones. In the grouping of gems, with regard to effects of lustre, colour, texture, etc. certain combinations often seen are far from ideal, while others rarely seen would be admirable. Thus a combination of the diamond and turquoise is not a proper one, since the opacity of the latter stone deadens the lustre of the former. The cat's-eye and diamond make a better combination, and so do the more familiar pearl and diamond. Colourless stones, such as the diamond or topaz, associate well with deep-coloured ones, such as amethyst and tourmaline, each serving to give light and tone to the other. Diamond and opal as a rule detract from each other when in combination, since each depends upon 'fire' for its attractiveness."

|

|

|

|

|

|

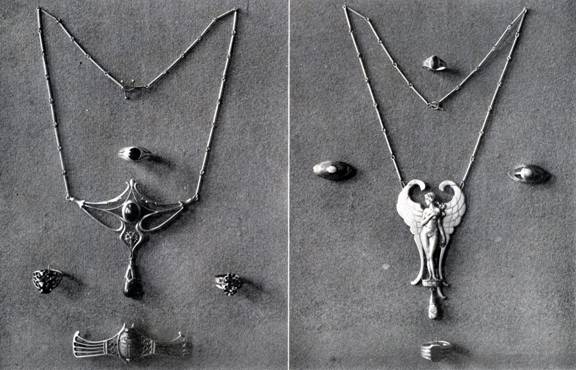

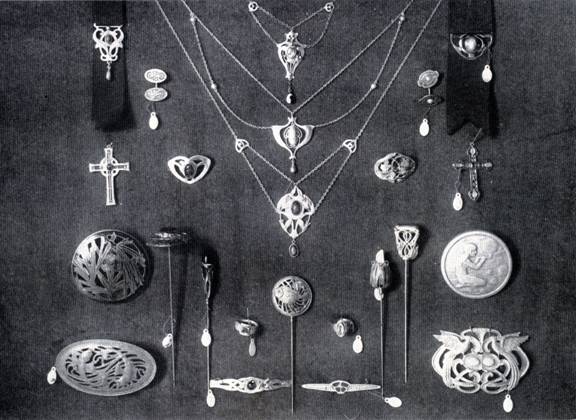

Work of students at Pratt Institute

While there are variations innumerable of design and device in mounting gems, there are practically but two basic methods, the mount a jour (two French words, meaning to the light) and the encased mount. The ordinary manner of setting gems in rings, the stone held by a circlet of claws, permitting a view of it, or through it, from all points, illustrates the a jour, or open, method. This is best adapted to transparent stones, exposing them freely to the light. The projecting claws of the open setting are slightly cleft near their extremities and these, under a pressure that inclines them slightly inward, pinch or grasp the stone at the girdle. Opaque stones, such as bloodstone, turquoise, or onyx, are usually set in the encased mount, in which the gem is set in a metal bed, with only the top exposed.

While to some degree anything fashioned by machinery is open to the detracting term "commercial," there is often much artistic merit in the designs issuing from the factories of manufacturing jewellers, but nothing can rival the charm of objects wrought solely and entirely by hand.

|

|

|

|

|

|

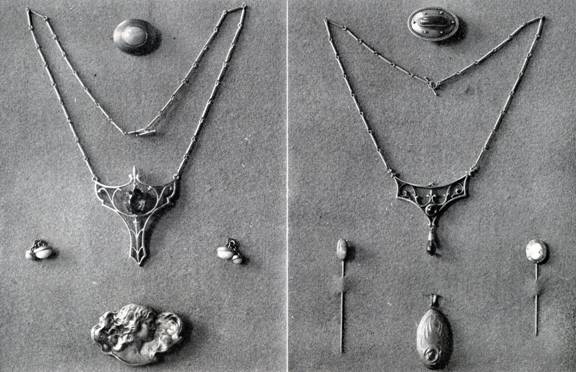

Work of students in Rhode Island School of Design

The work of the more expert of the students taking the jewelry course in Pratt Institute of Brooklyn, and at other educational institutions where this department of art and manual training is a serious feature, is a revelation of present attainments, and a hopeful sign that the jewelry of the future in America will conform more to true artistic ideals and serve less as a medium for mere ostentatious display. An exhibition of the work of students in the jewelry course was an attractive phase of the twenty- fifth annual exhibit of student products at Pratt Institute in June, 1908. The exhibits of the class in jewelry and metal-chasing were displayed in two large glass cases, and consisted of pendants, rings, bracelets, brooches, stick-pins, scarf-pins, buckles, and hammered copper work.

|

|

Prize Design: Work of Frederick E. Bauer, student, jewelry class, Cooper Union

A silver medal presented by Mr. Albert M. Kohn of New York City, as a prize for the most proficient student of the jewelry class, was awarded by a committee of trustees, who acted as a jury of award, to Mr. Carl H. Johonnot. The work exhibited by the winner of the medal included a number of fine rings, pendants, silver spoon, and stick pins.

For a description of the class in jewelry designing at the Pratt Institute, and also for excellent photographs of finished work executed and designed by students of the class of 1908, credit is given to Mr. Walter Scott Perry, Director of the Department of Fine and Applied Arts, of the Institute.

|

|

Gold pendant with topaz and pearl Gold ring with opals and emeralds Gold pendant with pearls

By Mrs. Ednah S. G. Higginson, The Society of Arts and Crafts, Boston

The first class in jewelry, hammered metal, and enamelling was organised in the Department of Fine and Applied Arts, Pratt Institute, in September, 1900, with Mr. Joseph Aranyi as instructor in day and evening classes. Mr. Aranyi at the time was one of the expert workers with Messrs. Tiffany & Company, New York City. He continued as instructor of the class, until June, 1904, when he resigned his position to accept one in Providence, Rhode Island.

In September of the same year Mr. Carl T. Hamann was appointed instructor in jewelry, and for some time has had full charge of all work of this class. He has proved himself an exceptionally fine instructor, and the quality of work has gained very rapidly under his instruction. Mr. Hamann is an expert jeweller by profession, being formerly connected with Durand & Company, Newark, N. J., and later with Tiffany & Company, New York. In 1889 he went to Europe and studied modelling in Munich for one and a half years, going from there to Paris, where he studied in the Academie Julian and the Ecole des Beaux Arts for two years. After his return to this country he became the head modeller for the Whiting Manufacturing Company, New York. Mr. Hamann was the sculptor of the statue of Justice which was one of the eight statues on the Triumphal Bridge at the Pan-American Exposition at Buffalo. At St. Louis he had a statue symbolical of Wyoming in the Colonnade of States, and he is also sculptor of the figure of Modern Art on the permanent Fine Arts Building. Mr. Hamann is a member of the National Sculpture Society. He brings to the students the knowledge and skill of a professional workman, combined with the originality and artistic appreciation of a professional artist.

In September, 1904, Mr. Julien Ramar became instructor in chasing and hammered metal work in the evening class, and also gave two half- days to the day class. Mr. Ramar was for several years chaser for Elkington & Company, England, and in America had been employed by the National Fine Art Foundry, the Archer & Pancoast Company, the Edward F. Caldwell Company, and other firms.

In September, 1905, Mr. Theodore T. Goerck took charge of chasing and hammered work in the day and evening classes and continued as instructor for two years.

Mr. Hamann at present is instructor in both day and evening classes. The classes have grown steadily and the work has increased in efficiency. Students have been very successful in securing employment. Many have opened studios of their own and fill orders that come to them from many and varied sources.

The courses are planned to meet the needs of those who wish to enter the trades involving enamelling, jewelry, repousse, chasing in precious and other metals, and the making of suitable tools required in such work. They give adequate training in modelling and design, in the application of designs to practical problems, the setting of stones, enamelling and finishing, and in the methods and practice of technical work in metal. Instruction is also given in medal work and in the preparation of models for reduction.

The increasing demand for applied art work in useful objects, and the difficulty experienced by manufacturers in securing the services of American artisans whose skill and knowledge are sufficient to guarantee good workmanship, present a trade condition which offers unusual opportunities for remunerative employment and advancement to those who have had the advantage of such training as these courses give.

|

|

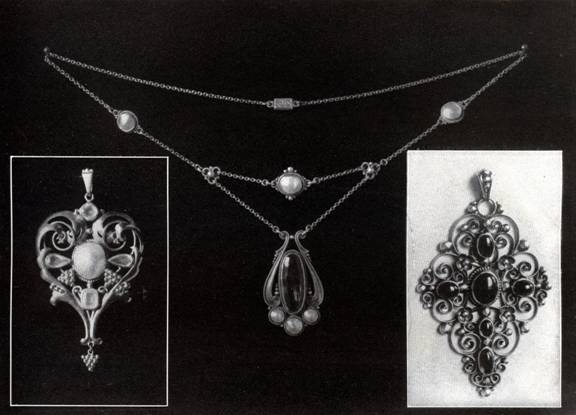

Oxidised silver necklace, pale yellow topaz, and white pearl blisters by Florence A. Richmond

Pendants by Frank Gardner Hale, The Society of Arts and Crafts, Boston

In this day of specialisation, the apprenticeship system is no longer adequate. The apprentice acquires little more than the skill necessary to meet the technical requirements of his trade; but, as the success of the ornamental metal worker depends quite as much upon his artistic conceptions and his designs as upon his skill in execution, the work of the shop must be supplemented by art instruction. By alternating the character of the problems given to the students, the applied work shows the inspiration that comes from a careful study of ornament, modelling, and the principles of design; and the work in modelling and design shows the adjustment and illumination that come from constant contact with practical problems.

The courses appeal to two classes of workers; to the apprentice who, by this instruction, can greatly shorten the period of his apprenticeship, and who can supplement the technical skill which he would gain in the shop by the work in modelling, drawing, and design; also to the art student who is turning his attention to work in the applied arts. The opening offered to such a man in this field exceeds that in almost any line of illustrative art work; and the demand for trained workers in the skilled trades in art applied to metals and the limited supply of such men make advancement practically assured to an earnest worker.

The rooms of the department devoted to the study and practice of jewelry and other forms of metal work are equipped as workshops with everything needful for practical and applied work.

The day course includes instruction in drawing, design, historic ornament, and in applied work in chasing and repousse, enamelling, jewelry, and medal work.

All work is designed and modelled in wax, cast in plaster, and then wrought in copper, silver, or gold. In the work in jewelry, silver is used from the first, students making rings with various stone settings, pendants, chains, scarf pins, bracelets, brooches, buttons, etc., the work being plain, chased, decorated, or set with stones.

In hammered metal work, students make their own tools and produce shallow and deep objects in copper and silver, including bowls, trays, spoons, and the like, with decorative designs and repousse chasing. Parts of objects, such as supports and handles, are also cast, chased, and applied as needed in the design.

Instruction is given in enamelling on copper, silver, and gold. All work is done in a thoroughly professional manner. Applicants are accepted only for regular and systematic work, and they must give evidence of originality, skill, and general fitness for the course. Certificates will be granted for the satisfactory completion of a day course of three years.

The classes meet for work daily, except Saturday; from 9.00 A.M. to 4:25 P.M. Instruction is given on eight of the ten half-day sessions. The tuition fees are $20.00 a term, with an additional laboratory fee of $3.00 a term for miscellaneous material used by students. There are three terms in each school year. The fall term opens the last week in September.

|

|

Development of a design by student at Rhode Island School of Design

The course provides for hammered metal work, wax-modelling, the application of relief ornament, and the finishing of casting in a thoroughly professional manner; the work being planned for advanced students as well as for beginners. Instruction is given in the modelling of objects in sheet metal, the making of tools, repousse, or relief ornament in flat and hollow ware, and the chasing of ornament in bronze, brass, silver, and gold. Instruction is also given in jewelry. The class meets on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday, from 7.30 to 9.30 P.M., from the last week of September to the last of March. The tuition fee for the evening course is $15.00 a season of six months, which includes all practice material used by students in class.

Students and alumni of Pratt Institute have organised The Pratt Art Club, which its members otherwise quaintly designate as "Ye Brooklyn Club of Ye Handicrafters"; in its exhibitions, held at the club's rooms near Pratt Institute, are shown some attractive specimens of the work of these crafters.

There is a course in jewelry designing at Cooper Union in New York City under the direction of Mr. Edward Ehrle. The Cooper Union class meets tri-weekly, in the evening, for a two hours' session. The work begins with easy geometrical designs; original work by the pupils is constantly encouraged. The school year begins the second Monday after September 15th and ends about May 15th. The full course requires about three years. At the conclusion of the term in the year 1908, a cash prize offered by The Jewellers' Circular-Weekly was awarded to Mr. Frederick E. Bauer for his excellent work.

|

|

Finished work of students at Charles B. Dyer's Arts and Crafts School, Indianapolis

A resource of value to the artistic designer of jewelry in and near New York City is the Cooper Union Museum for the Arts of Decoration, a subsidiary institution of this famous old hall of education that is now, although progressing in its acquisition of valuable exhibits, of incalculable value to the arts and industries of America; the usefulness of this institution is however restricted, because it is not well known. It is probably a safe assumption to say that not one person in many thousands of the inhabitants of the metropolis is cognisant of the existence of such a treasure-house, which is available to all earnest seekers after information, ideas, and material for the betterment of art, and under conditions impossible to excel in providing the Greatest opportunity and freedom to all who will avail themselves of it. The contents of this museum would astonish thousands who are familiar with the broadly advertised contents of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the feeling of regret that comes over the appreciative visitor to the Cooper Union Museum suggests the reflection that a little adept yet dignified promotion of publicity would be beneficial to the efficiency of this institution. A strong feature of this working museum is a collection of encyclopedic scrap-books, open, like all else here, to all applicants for permission to use them; the scrap-book covering jewelry shows many excellent designs, fertile in ideas for bracelets, clasps, combs, chatelains, lockets, crowns, tiaras, head ornaments, knots and bowknots, dress and engraved ornaments, earrings, belts, girdles, hoops, rings, necklaces, pendants, seals, sceptres, and watches.

While the bibliography presented in this volume is extensive and of wide scope, unfortunately, but a few of the books listed are to be found in the average public or institutional library. A valuable resource for the students at Pratt Institute or Cooper Union, or any one who would delve as deeply as possible into the subject of jewelry, is the Society Library in University Place, near Thirteenth Street, New York City. This, Manhattan Island's oldest library, was founded by King George II., and his representative who was at the time the royal governor of the Colony of New York. The family of ex-President Roosevelt have been benefactors of the library for six generations, and he is at this time an active member of the board of trustees. Although not a public library, the superb collection of art books, selected with special reference to the requirements of handicraftsmen and artists, is always open to designers. There is a large endowment fund for the support of the art book department, which is known as "the Greene foundation."

The productions of designers and workers in jewelry seen in the annual exhibitions now held by the National Arts Club, in collaboration with the National Society of Craftsmen, in the galleries of the club at 119 East Nineteenth Street, New York City, prove the good work that is being done by individuals and members of various schools and classes; these include the jewelry class of the New York Evening School, and the jewelry class of Miss Grace Hazen of Gloucester, Mass.

At Newark, N. J., an industrial city which includes among its industries considerable jewelry manufacturing, there is the Newark Technical School, supported by appropriations from both the city of Newark and the State of New Jersey, which has a valuable course for workers in jewelry.

In Boston there is continuous encouragement to designers of art jewelry in the work and influence of the Society of Arts and Crafts, Boston, incorporated in 1897, and which holds exhibitions semi-annually. A recent exhibition of this society included a valuable and most interesting display of American jewelry, the feature of which was a large collection of excellently drawn, exquisitely designed, and well executed pieces from the Copley Square Studio of Frank Gardner Hale, the exhibit occupying one end of the exhibition gallery. Mr. Hale's products are not only definite in design, but the construction of his mountings of gems is practical and would satisfy the mechanical requirements of manufacturers of jewelry commercial, which a good deal of the work of exponents of arts and crafts jewelry would not. New Yorkers at home have had an opportunity to see some of Mr. Hale's remarkable work at an exhibition at the Clausen Galleries. Among the designs exhibited, necklaces, chains, brooches, and pendants predominated; there were numerous crucifixes in silver, some of them containing precious and semi-precious stones. In the number and excellence of these crucifixes, Mountford Hill Smith took the lead among the exhibitors. Marblehead's handicraft shop was represented by the work of H. Gustave Rogers. Commendable work was shown by Jane Carson and Theodora Walcott. Notable exhibits were those of Elizabeth E. Copeland, Laura H. Martin, and Martha Rogers. Ingenious schemes of colour in small enamels were shown by Mabel W. Luther. William D. Denton of Wellesley exhibited "butterfly jewelry "in which the wings of the butterflies are protected by rock crystals set in gold mounting. Jessie Lane Burbank and Florence A. Richmond from the workshop in Park Square exhibited pieces deserving honourable mention.

The officers of this society are: President, H. Langford Warren; Vice-Presidents, A. W. Longfellow, J. Samuel Hodge, and C. Howard Walker; the Secretary and Treasurer is Mr. Frederic Allen Whiting of No. 9 Park Street, Boston.

In Providence, R. I., a centre of the great jewelry manufacturing interests of New England, there are various opportunities for the aspirant for technical proficiency in the designing and making of jewelry; there is a jewelry class in the Young Men's Christian Association, a course in the regular curriculum of the public Manual Training or Technical High School, and an important department of the Rhode Island School of Design is that devoted to silversmithing, jewelry designing, and shop work. For many years the New England Manufacturing Jewellers and Silversmiths' Association has annually offered a sum of money, to be divided into several prizes, to stimulate students at this school of design to systematically study the designing of jewelry and silverware.

The Bradley Polytechnic Institute of Peoria, Ill., is an institution important in its relation to the present subject, having a jewelry course that has attained and deserves a wide reputation; the course extends over a period of from three to five months' duration. The instruction includes the making and finishing of oval and flat gold band rings, signets, modelling for casting, designing and production of jewelry, and all such repairing as is called for in ordinary jewelry store practice.

At Indianapolis, an indefatigable pioneer in the instruction of ambitious artisans in the precious metals is Mr. Charles B. Dyer, who has inaugurated a local representation of the arts and crafts movement with a school and a shop in which the hand-made jewelry of the students and graduates of the school is sold. About forty students were enrolled in the class of 1908. At a semi-annual exhibition of the students' hand-wrought products about three hundred pieces were exhibited, including copper and bronze work; the items in the exhibition were inspected with lively interest by several hundred visitors, whose commendations were enthusiastic and freely bestowed.

In response to a request, Mr. Dyer supplied an interesting account of the beginning and progress of this Middle West school, that is successfully uplifting ideals and enabling the earnest and ambitious young worker to design and make jewelry that come up to an artistic standard, as follows:

Three years ago there was formed in Indianapolis a "Society of Arts and Crafts "with a very promising membership. A house was rented and furnished and salesrooms opened. The movement grew and a large number of the right kind of people became interested. Unfortunately, however, there were so very few of the members who were craftsmen or in any way producers of salable stuff that everything had to be gotten on consignment from outside. Like so many other associations that have tried the commission plan, and through mismanagement, the society did not live long.

During its life, however, it had started a number of earnest people to thinking and had given them the desire not only to raise their standards of beauty in both useful and decorative objects, but to express their own thought and individuality. My father and I had taken great interest in the movement and had made a number of pieces of jewelry for the salesroom. When we were asked to start a class, teach the use of tools, and show how original designs could be executed in metal, we were glad to undertake the work. We started with a class of five, all of whom were art teachers in the high schools here. I might say in passing we had over seventy-five applicants this fall.

As we conduct a manufacturing jewelry business, our shop is well equipped for all kinds of metal work. We have a bench for each worker where all the small tools, wax blocks, hammers, and punches are kept and also several large vises and anvils for the large copper work. Polishers, rolls, annealing furnace, enamelling furnace, and all kinds of other tools make the shop complete enough for any work.

As the class is only a sort of pastime for us we have it at night and charge almost nothing for tuition. The worker first designs the piece and selects the stones and material to be used. After the design has been criticised it is transferred to metal and executed. We have no lectures or class problems. All the pieces and all the criticism are individual. In that way we do not allow any worker to leave a piece until it is well executed.

Most of the workers are so interested in the work that they have their own workshops and tools at home, and a number of them have not only produced some very creditable pieces but have made good money in doing it. At the end of each term, that is just before Christmas and in June, we have an exhibit and sale of the class work. We send out copper plate invitations and make a social affair of it and succeed in selling most everything produced during the term. We have created a wide interest in the movement and are much encouraged to carry it along.

From many sources students are now receiving aid, encouragement, and information which but a few years ago was unheard of in America. A case in point is the offering annually by Herpers Bros., a business concern extensively engaged in the manufacture of parts of commercial jewelry, in New York City and Newark, N. J., of gold medals to the most proficient students in five leading technical schools in the United States.

At the suggestion of Hon. Oscar Straus, Secretary of the Department of Commerce and Labour, it is said: Prof. John Monaghan, for a long time a representative of the United States Government, in the consular service, has delivered series of lectures for jewellers' associations and at technical institutions which have jewelry classes or courses. While consul at Chemnitz, Germany, Prof. Monaghan devoted much time to a study of the technical schools of the German Empire.

In the opinion of Mr. Gutzon Borglum, as lately expressed in The Craftsman, the art school of to-day will pass and be supplanted by the school of crafts, with the predicted result that there would be immediate improvement in our wares, textiles, furniture, interior decorations, and ornaments of every kind, and that, instead of the host of unsuccessful artists of to-day, there would be successful master craftsmen, putting life and beauty into our liberal arts, invaluable citizens, and, incidentally, that these graduates of the schools of crafts would be economically independent and contented. Mr. Borglum points out that the Metropolitan Museum of Art with its collections would form a nucleus and a foundation for this useful innovation.

![Prize Design: [Arts & Crafts] Work of Frederick E. Bauer, student, jewelry class, Cooper Union](Arts_&_Crafts_Jewelry_files/image012.jpg)

![Development of a[n Arts & Crafts] design by student at Rhode Island School of Design](Arts_&_Crafts_Jewelry_files/image015.jpg)

![Finished [Arts & Crafts jewelry] work of students at Charles B. Dyer's Arts and Crafts School, Indianapolis](Arts_&_Crafts_Jewelry_files/image016.jpg)